Child Development & Technology

Digital Literacy: What Does it Mean to be Literate in the 21st Century?

Early exposure to everyday digital devices is giving young children access to a rich variety of new forms of interaction. The way we share and convey information is changing, as is the way in which our notion of reality is presented, manipulated and perceived. So while we as adults continue to immerse ourselves in the comforts and benefits of new technologies, is the way children now acquire language undergoing a major transformation before our eyes?

Theories of Language Acquisition

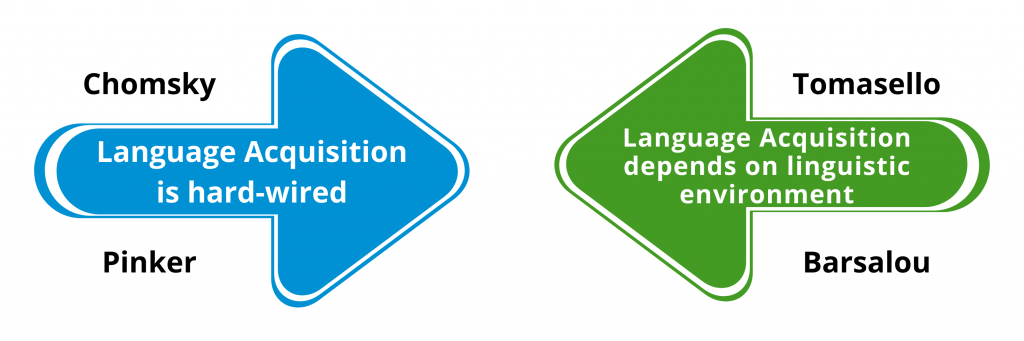

Discussing existing theories of language acquisition (see Figure 1), Vulchanova et al (2017) note that the most influential of these theories seem to offer two differing accounts. Both Chomsky (1965) and Pinker (1994) suggest that the human brain appears to have a hard-wired capacity for language learning, whereas Tomasello (2003) and Barsalou (2008) consider a child’s language acquisition to be a more flexible arrangement primarily influenced by the linguistic environment, especially child-adult communication and other interactions.

Explaining these latter theories in more detail, Vulchanova et al comment on what their term ‘other interactions’ implies:

‘This interaction leaves multiple traces provided by a number of modalities (auditory, visual, haptic etc.) and helps consolidate knowledge in the brain by strengthening the neural networks that support learning and the use of knowledge.’ (Vulchanova et al, 2017)

Nevertheless, the same authors warn that:

‘Exactly how input received from multiple, and multi-sensory in nature sources, interacts in both knowledge acquisition and use is, however, still poorly understood.’

Driving home the point about today’s children being influenced by, and interacting with, new channels and modalities, they ask three pertinent research questions:

‘1) How should traditional theories and models of language acquisition be revised to account for the multimodal and multichannel nature of language learning in the digital age?

2) How should existing and future technologies be developed and transformed so as to be most beneficial for child language learning and cognition?

3) Can new technologies be tailored to support child growth, and most importantly, can they be designed in order to enhance specifically vulnerable children’s language learning environment and opportunities?’ (Vulchanova et al, 2017)

Digital Literacy: Learning A New Language

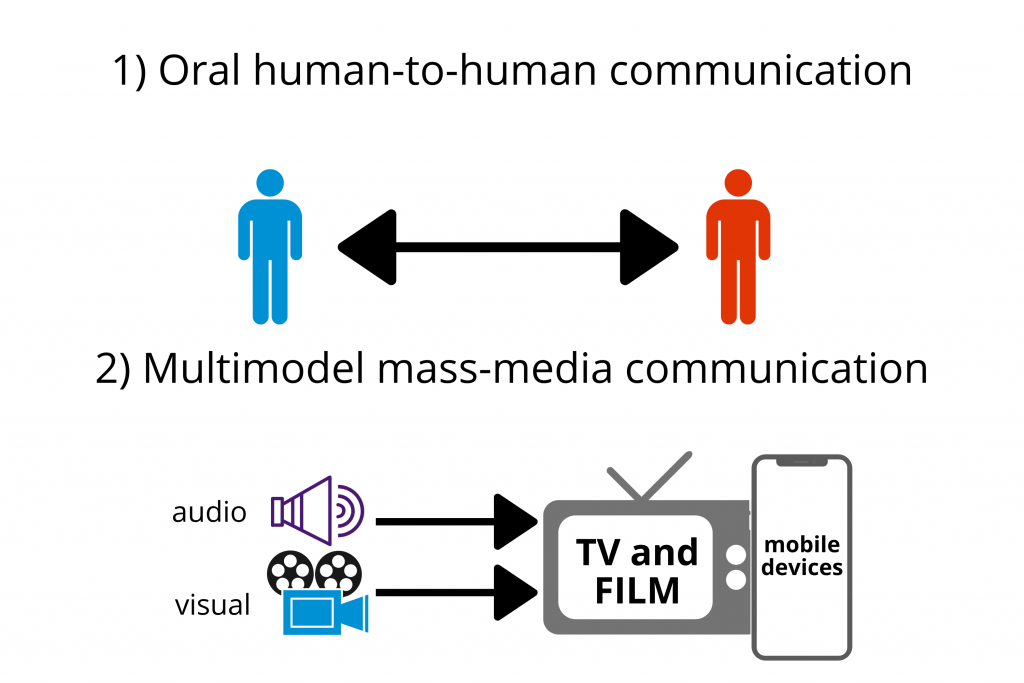

Researchers such as Willie (1979) long ago suggested that mass media technologies of all kinds were creating a new composite language which was being delivered and received in new ways. As Figure 2 shows, this differs in several important respects from the kind of child-adult learning encounters our early years provision still often assumes.

In fact, some contemporary observers suggest that with the emergence of text emojis, as well as most public signage, basic device instructions etc. which include prominent symbols, icons and other visual cues, we are heading towards a new age of hieroglyphs which is destined to have a profound effect on the grammar and syntax of our language. This, of course, has major implications for young children acquiring language skills.

Earlier research on the effects of mass media exposure has not always delivered much clarity. For example, Zimmerman and Christakis (2005) report that observations of infants and parents watching TV together suggested child-directed speech declined, with an increased use of short phrases and one-word responses. Yet Ferguson and Donnellan (2014) noted that infants with no mass media exposure had lower language development scores than infants who had experienced some exposure.

What many observers seem to be saying is not that all this is good or bad, but that it is the current lived experience of many young children, and yet is poorly researched. That means the childcare sector in turn remains poorly informed about trends and developments.

Digital Literacy: SEND Applications

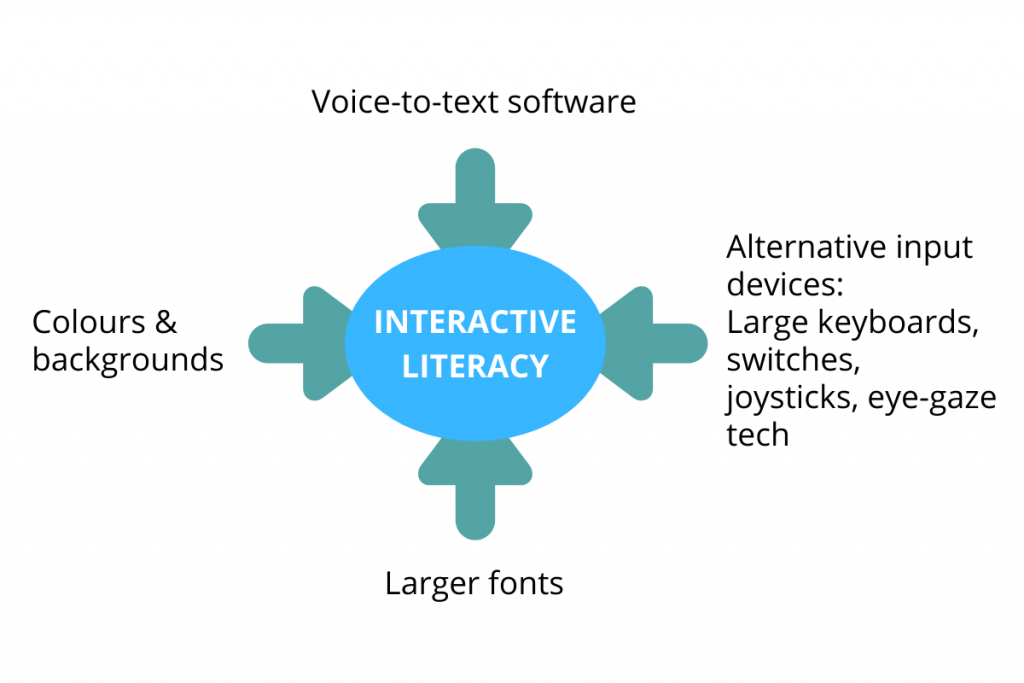

No discussion of language acquisition should ignore SEND (Special Educational Needs and Disabilities) applications where technology can amplify, enhance and endlessly repeat operations to support language development among those with impairments (See Figure 3). Here, it can be argued that the essential help and life-changing empowerment such technology can provide so often transcends whatever other limitations there may be.

For instance, who could deny the benefits of empowering individuals via features such as joysticks and eye-gaze technology, or large fonts and voice-to-text-software? And surely a voice-activated assistant (Siri, Alexa et al) or a digital-signing avatar for the hearing-impaired, must be among the best possible uses for such tech developments? The same goes for handheld tablets where not only larger fonts but also different coloured backgrounds can be called up at a keystroke to assist those with dyslexia.

Digital Literacy: Technology in the Early Years

While some may personally view the impact of the digital world on all educational practice as a transitory phase with yet unproven results, this should never be used as an excuse to downgrade its importance. But likewise, just because there is a tech solution doesn’t mean it must always take priority. While such decisions should always be made in the interests of the child, too often outcomes directly correlate to the confidence and experience of the adult staff in any particular setting.

Furthermore, limiting a child’s access to early years technology which genuinely enhances language acquisition, on the grounds that it becomes ‘more relevant when they are older’, is denying children the preparation they will need for the future digital world they are destined to be part of.

There is already evidence that children learn a great deal from digital devices used at home which are rarely found in pre-school settings.

‘The National Literacy Trust’s 2016 early years research (Knowland & Formby, 2016) shows that touchscreens are much more prevalent in homes than in early years settings and that parents report a higher degree of confidence in using digital technology to read with their children than that of practitioners, who usually report lower confidence in their own skills and that of the children they care for.’ (Billington, 2016)

This not only ignores a powerful and relevant mode of learning, it also does nothing to address the ‘digital divide’ where children of poorer families are allowed to fall behind simply because of their disadvantageous home circumstances:

‘By the age of five, a child’s vocabulary will affect their educational success and income at the age of 30.’ (Feinstein & Duckworth, 2006)

Addressing such issues, Billington (2016), on behalf of The National Literacy Trust, comments:

‘Flewitt et al. (2014) rightly state that technology alone does not make a difference to children’s learning, but instead there needs to be careful planning from early years teachers to deliver supportive activities that will meet intentional learning goals or outcomes. Plowman (2016) advises that play and use of technology should not be seen as separate topics, with good practice pedagogy moving away from, “teacherly guidance” and towards open-ended exploratory play.’ (Billington, 2016)

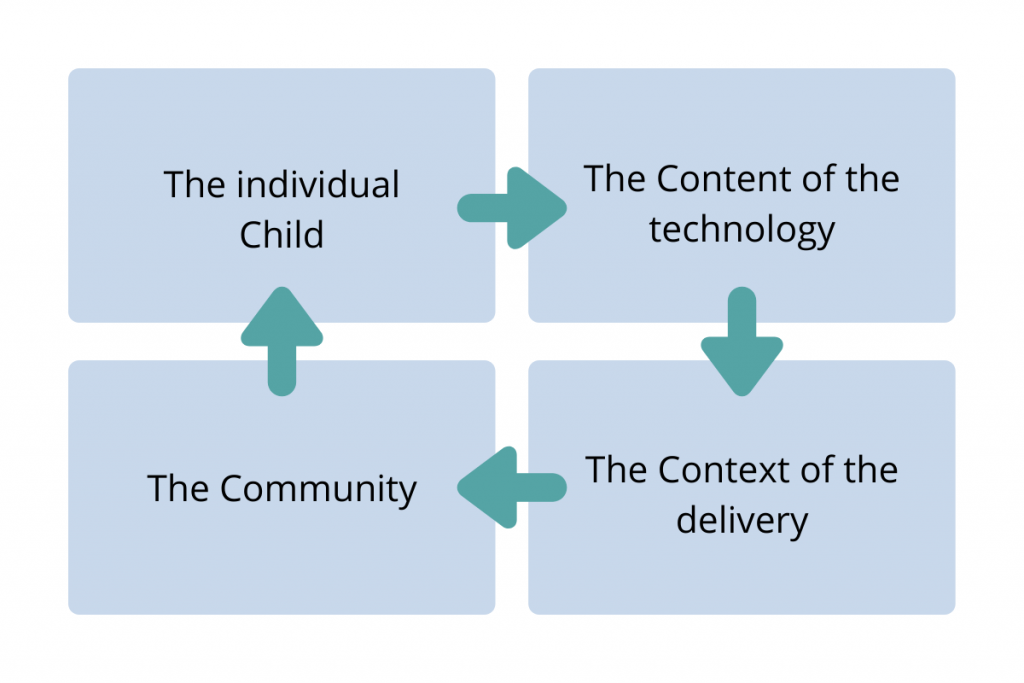

One framework which can help professionals to make choices and strike a realistic balance is the ‘four C’s’ proposed by Guernsey and Levine (2015) (See Figure 4 below). This advice reminds professionals that any tech learning solution must:

- Be appropriate to the Child;

- Offer high-quality content;

- Fit the Context of delivery and present an experience relevant to a child’s ‘real’ life; and

- Support the Community’s needs and interests as regards improvements in learning and literacy.

The Importance of Focus

In recent years, it has been noticed that significant numbers of young children enter early years settings with under-developed language skills (ICAN, 2007). The strong implication here is that, even though children listen to speech at home, watch TV and possibly engage with additional digital media, without regular and stimulating two-way communication the development of their own speech will be impaired.

So in terms of supporting language acquisition, deploying any technology based solutions demands a carefully focused approach. Dryden reminds us how essential it is to get this right:

‘… it is important for technology to be used as a tool for two-way communication; passive listening is not as powerful as experiences where children are encouraged to be active participants.’ (Dryden, 2017)

Advice from the National Literacy Trust 2016 review underlines the points made above, and cautions:

‘… researchers, early years workers and specialists all agree that [technology] should not be used as a replacement to adult interaction. Rather, it should be used as another tool for teaching, like a book. In addition, we know that, if used correctly, technology can play an important route into reading for certain groups of children, such as those from disadvantaged backgrounds and boys.’ (Formby, 2014)

Communication Language and Literacy Best Practice

Strong communication and language skills prepare the ground for later literacy acquisition. So technology should be used to support children and provide opportunities for them to communicate their ideas and feelings. What is more, it also:

‘… enables them to produce unique speech, providing a platform for them to discuss, narrate, recount, explain, problem-solve and negotiate verbally with others.’ (Dryden, 2017)

Within settings, specific communication and language skills can be practised and developed by a variety of means, including:

- using walkie-talkie sets, mobile phones or even ‘talking tins’ to contact others – especially to communicate with another person with whom they have no visual contact (a skill which can be daunting for many children);

- employing microphones and recording equipment to express ideas and feelings and relay instructions, before critically listening back and perhaps using delete and re-record to edit and improve their results;

- communicating via Skype interactive video calls and creating podcasts to capture their input on various topics and tasks;

- exploring karaoke software and equipment used to join in performances of well-loved songs and nursery rhymes.

An IWB (Interactive Whiteboard) is an especially powerful tool which can be used in a variety of different modes and settings:

– to support the learning of small groups of children (with adult supervision);

– as an interactive focal point at circle time;

– to introduce topics which demand visual resources beyond the classroom.

An IWB can be used to spark discussion or debate, and can also be used to present children’s photos and videos. In this latter role, an IWB could be used, for example, to present a series of images of earlier outdoor activities at the setting which the children could then put into the correct sequence.

The Way Forward

In summary, the National Literacy review (2016) encourages settings, practitioners, parents and those with wider interests to ponder five specific questions as a means of mapping the way forward:

- ‘How can technology begin to be embedded in early years pedagogy, based on what we already know about child development and emergent communication, language and literacy skills?

- What tools will practitioners need to do this and how can we support them?

- How can practitioners work with parents to link or enhance technology use across the setting and home?

- How can messages which promote positive behaviors when using technology be shared with parents?

- Do early years environments need to be adapted to allow for the use of technology?’ (Billington, 2016)

You must be logged in to post a comment Login