Childcare Environments

A Modern Paranoia: Perspectives on Risk

“A ship is always safe at the shore – but that is NOT what it is built for.”

― Albert Einstein

Just like generations of skilful mariners, modern childcare professionals are keenly aware of risk, especially as risk assessments probably govern many aspects of their daily practice. And should they ever become the slightest bit complacent, the media elements in our modern society will continue to regularly drip-feed stories of accidents, dangers and abuse of every kind which, theoretically at least, have the potential to threaten the well-being of every child. All too soon this can lead to the growth of a stultifying ‘risk-aversion culture’ which can have a devastating effect on the growth and development of children.

The risk concept

Acknowledging that tragedies do occur, there are many who nevertheless feel the term ‘risk’ has acquired inappropriate overtones – as for example in the phrase ‘a child at risk’ – which can all too easily skew our perceptions. In the experienced opinion of insurance-industry risk professionals:

‘Risk per se is neither good nor bad; rather it is an expression of probability – the likelihood of a particular outcome, positive or negative.’ (Corley & Utermann, 2015).

Thus our society’s current fears are often needlessly raised, and sometimes shamelessly exploited, by the casual, everyday distortions of this concept. In reality, it is often far more accurate and helpful to visualise the word ‘risk’ at the mid-point of a continuum in which hazard and challenge reflect negative and positive extremes:

Figure 3.1 The concept of a risk continuum

This view is supported by Morland (2015) who has noted the ‘delusional zeal to stamp out … the neutral idea of uncertainty [and replace it] with the negative one of hazard’. ‘Indeed, your thesaurus will tell you,’ she warns, ‘that “hazard” and “risk” are one and the same, but do not be fooled; they are not.’

Risk assessments

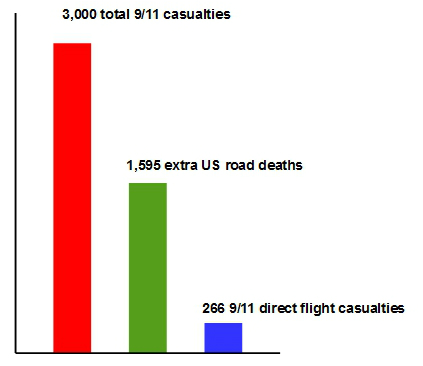

It is never easy to think rationally when we become unreasoningly fearful about risk, and as Corley & Utermann again observe, ‘[when] profound risk aversion becomes a habit [it] can undermine good decision making’. This truth was exposed by the psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer (2006) who carefully researched US travel habits in the wake of the 9/11 disaster in 2001. Predictably, the US public mostly abandoned air travel during the year following those terrorist attacks. Gigerenzer’s data, summarised in Figure 3.2 below, shows that the collective switch from planes to cars resulted in 1,595 extra road deaths over the 12-month period (after which, figures then fell back to the previous normal levels).

Statistically, air travel is dramatically safer than car travel, so in effect, each of these unfortunate people made a decision they imagined was ‘safe and wise’, with lethal results. Dr. Howard Gardner calculates that 1,595 fatalities is ‘over 50% of the 3,000 death toll caused by the 9/11 atrocity’, and ‘six times higher’ than the 266 victims aboard the hijacked aircraft, and comments:

‘[the families] still think they lost husbands, wives, fathers, mothers, and children to … traffic accidents we accept as the regrettable cost of living in the modern world … They didn’t … It was fear that stole their loved ones.’ (Gardner, 2009).

Well-intentioned parental anxiety and fear, many now believe, is denying children opportunities to become risk-wise through learning to refine and trust their own judgements.

As politicians and the media are well aware, the impact of bad news is mostly personal and cultural, and as such it regularly colours and distorts our thinking. What is more, (as fund-raising advertisers for international aid agencies know very well) most of us respond emotionally to a depiction of one distressed child, whereas we find it harder to grasp the full tragic implications of large-scale death tolls to the same degree, leading some to describe such statistical reports as ‘people with the tears dried off’.

Figure 3.2 Aftermath of the 9/11 atrocity (Inspired by Gigerenzer, 2006)

Contemporary exposure to risk

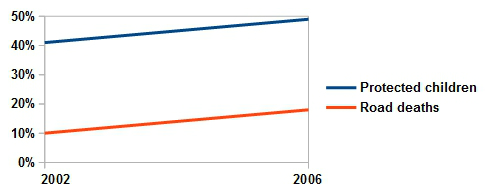

Similar comparisons have been made about the risks children now face in the modern world. Guldberg, for instance, made a ‘positive correlation’ which explored the relationship between child pedestrian fatalities and the amount of parents unwilling to allow their children to cross a road alone. Figure 3.3 shows that, over the same four-year period, totals for pedestrian road deaths among seven-to-ten-year-olds and the growing number of overly-protected children each increased by 8%. One implication of these figures is that, having little practical experience of road hazards, this group of child pedestrians therefore became more accident-prone.

Figure 3.3 Positive correlation of road deaths and protected children (Inspired by Guldberg, 2009)

Well-intentioned parental anxiety and fear, many now believe, is denying children opportunities to become risk-wise through learning to refine and trust their own judgements. As de Botton puts it:

‘An age obsessed by safety has opened up a collective new danger: the sclerosis that comes from putting security above all other virtues.’ (de Botton, 2015).

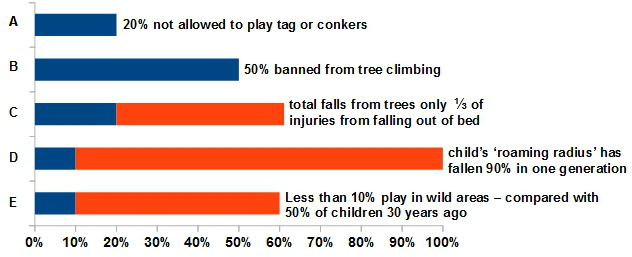

The withering effect this doom-laden atmosphere is having on the ‘risk muscles’ of a today’s young children has been documented by Moss (see Figure 3.4) who compares some of our present watchful, stringent attitudes to children’s outdoor play with the freedoms children enjoyed in the past:

Challenge as a catalyst for risk awareness

As all parents and those delivering early years care will know, younger children are naturally wired to flourish via endless cycles of ‘risk – grow – repeat’ activity. Explaining some of the many benefits this brings, Tovey reminds us:

‘Babies would never learn to crawl, negotiate steps, stand up, or children learn to run, ride a bike and so on without being prepared to take a risk, to tumble and to learn from the consequences. Learning to navigate space, people and objects requires risk and a willingness to try things, have a go and make mistakes.’ (Tovey, 2011).

One particular aspect of this play world of discovery is the high-octane exposure to challenge and adventure which is termed ilynx or ‘dizzy play’ – and which, for many, continues into adult life. The Greek word ilynx literally translates as ‘whirling water’ and relates to the swirling sensory rush young children are drawn to enjoy and constantly explore through activities such as being tossed in the air, balancing precariously, and many others where the boundaries between joy and fear, success and failure, risk and reward are blurred – or even temporarily suspended – pending a safe outcome and a heightened sense of satisfaction, well-being and self-worth.

Dweck (2000) has described this early-childhood behaviour as building the core components of a ‘mastery disposition’ which will support a lifetime of learning. If this facility is not allowed to develop, Dweck believes, it is soon replaced by an acquired ‘helplessness’. This, she claims, is often made far worse by the persistent communication of parental anxieties. Rather than pursuing the impossible goal of absolute safety, Dweck argues that enjoyable challenge is by far the best response because:

‘It doesn’t help a child to tackle a difficult task if they succeed constantly on an easy one. It doesn’t teach them to persist in the face of obstacles, if obstacles are always eliminated.’

Defining The Outdoor Classroom – Download Free eBook

Risk and safety in practice

The legal doctrine of ‘in loco parentis’ (i.e. behaving like a responsible parent) is often taken by childcare workers to mean they must attempt to make every outdoor environment and play experience 100% safe. Whilst it would be reckless to suggest they should be unsafe, the crux of the matter is: what is expected of professionals is that they understand the dangers and have properly assessed and adjusted the balance between challenge and benefits. This entirely fulfils their ‘duty of care’ – which simply means acting in the same responsible manner as any reasonable adult would. To rule out age-appropriate challenge is effectively to deny children opportunities to develop and become risk-wise. Many therefore believe such actions could be deemed to act against a child’s best interests, and thus would constitute a direct breach of the duty of care. As Solly points out:

‘Offering opportunities for risk, challenge and adventure which have been suitably risk assessed and considered as purposeful by the setting is far safer than children seeking out those not designed for them in places which are far from ideal and may lead to serious harm.’ (Solly, 2015).

Proactive policy

Childcare professionals cannot afford to remain neutral where risk is concerned. Ofsted for one will expect to see this feature positively addressed and effectively put into practice. Though many parents will, understandably, have their own perspectives and priorities, it is surely the duty of any responsible institution to provide leadership by fostering a ‘best interests’ culture. Demonstrating to parents that there is always a 360-degree assessment of challenge and adventure, as well as highlighting the longer-term benefits, is the best way to win support for such life-enhancing initiatives which are deservedly at the very heart of playing and learning outdoors.

References

1 Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment Login