Child Development

Music in Early Years and Holistic Child Development

Now that most of us live in a 21st-century global village it is tempting to imagine such worldwide connectivity is proof we are already masters of communication. But ironically, many of us now live among comparative strangers with our extended families scattered far and wide. Yet, in reality, we are little more than two generations away from a mature society of close-knit, family-oriented communities following a life pattern which had slowly evolved over thousands of years. So, biologically speaking, it’s hardly surprising our children continue to be born hard-wired and ready to reap the benefits of a stable, culturally rich environment.

Elsewhere, there are populations less fragmented than ours whose young children still enjoy growing up in a world to which they are so naturally adapted. For instance, the word ‘ngoma’ in both the Zulu and Swahili tongue refers to integrated activities in those cultures involving song, dance and play, and rarely makes any distinction between them. In these, and many other older traditions around the world, children learn that singing, movement and play are seamlessly interconnected strands of one social activity. Here it’s accepted, and celebrated, that the joy of movement can make you want to sing, that hearing music can make you want to move, and that listening to music can cause you to feel things – even before you have the power to speak and understand your own language.

Music in early years: An intuitive ability

Speaking of this phenomenon which ‘lies so deep in human nature’, neurologist Oliver Sacks comments:

‘… music has great power, whether or not we seek it out or think of ourselves as particularly “musical.” This propensity to music … shows itself in infancy, is manifest and central in every culture, and probably goes back to the very beginnings of our species. It may be developed or shaped by the cultures we live in, by the circumstances of life, or by the particular gifts or weaknesses we have as individuals …’ (Sacks, 2008)

‘The potential of music in early years settings is often unrecognised or at least undervalued and the contrasting attitudes of staff towards mark-making and music-making are striking. – Mary Fawcett

Adding further detail, Professor Colwyn Trevarthen, a specialist who studies young children’s innate understanding of music, suggests humans are born with a ‘communicative musicality’. It is this facility, Trevarthen argues, which enables even very young children to recognise and use auditory patterns and cycles to create ‘narrative structures’, often ‘many months before words make any sense’. Having collected much powerful video evidence of interactions between mothers and infants, Trevarthen has no doubt he has regularly observed pre-lingual infants uttering and responding to:

‘… patterns, that seem to be the material of human thinking, and problem solving, and grammar of language, all of this kind of dynamic patterning that makes things happen through time, and makes them predictable to other people.’ (Trevarthen, 2010)

Negative bias?

Whilst music does have a certain profile in most early years childcare, Mary Fawcett, Retired Director of Early Childhood Studies, University of Bristol, points out that its true power and significance has been consistently underestimated:

‘The potential of music in early years settings is often unrecognised or at least undervalued and the contrasting attitudes of staff towards mark-making and music-making are striking. Most adults are relaxed about offering mark-making activities such as drawing and there is widespread appreciation of young children’s self-initiated representations. But spontaneous musical behaviours in play situations often go unrecognised. These musical explorations and fascinations are rarely provided for and their possibilities developed. Indeed organising creative activities involving music often seems to present challenges.’ (Fawcett, 2012)

For the sake of clarity, this present discussion is not about nurturing musicians, any more than prompting young children to develop their language abilities is about promoting poetry. What it does seek to highlight is a distinct reluctance among early years educators to utilise the musical aspects of this inbuilt developmental mechanism – a refusal to adopt and exploit the ngoma principle – which thus ignores a powerful educational tool, impoverishes the early years experience, and artificially limits the possibilities for child development.

What music education professionals say

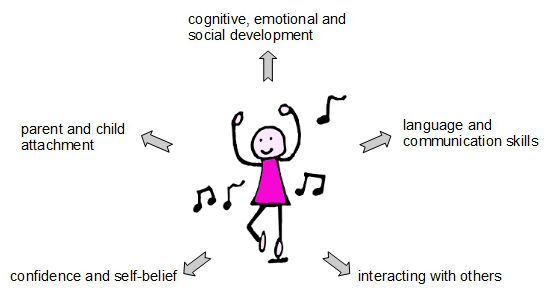

Underlining the positive effects of a music-enriched approach, the Music Education Council (MEC) have listed some of the major developmental benefits to be gained, as summarised in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1 Benefits of a music-enriched educational approach (Inspired by Griffiths, 2011)

Moving on to identify what they considered to be present shortcomings centred on a lack of professionalism, the MEC note five key issues which early years provision should address:

1. The National Plan for Music Education does not include Early Years provision.

2. There is a need to both inform parents and carers about the latent potential of music in the early years, and also to find ways to promote their active engagement, as well as encouraging settings to adopt a multi-agency approach.

3. The present broad range of early years settings and diversity of business models impedes the establishment and sharing of consistent, well-informed good practice.

4. From a music enhancement perspective, the sector is notably lacking in fit for purpose training qualifications and CPD opportunities.

5. Despite an obvious need, the sector often struggles to promote and celebrate cultural diversity.

Similarly committed to the role of music within any holistic learning environment designed for the early years, the National Association for Music Education (NAfME) offer their own position statement on early childhood education. Once again, the advice is that:

‘Musical experiences should be play-based and planned for various types of learning opportunities such as one-on-one, choice time, integration with other areas of the curriculum, and large-group music focus.’

Underlining the contention that, whilst having their own unique interests and abilities, all children have music potential, NAfME nevertheless point out that each child will always want to interact with musical materials in his or her own way:

‘One child may display sophistication and confidence in creating songs in response to dolls. Another child, in the same setting, may move the dolls around without uttering a sound – but this “silent participator” leaves the area content in having shared the music play. The silent participator often is later heard playing in another area softly singing to a different set of dolls – demonstrating a delayed response.’ (NAfME, 1991)

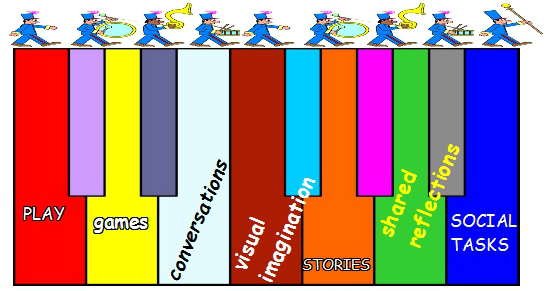

Given the opportunity to do so, children will absorb, copy and create musical structures within the bubbling, babbling flow of playful events which constitute their daily work. They will always learn best in pleasant physical and social environments where fun is a non-negotiable outcome and a range of active, manipulative and creative modes of learning are employed – the ngoma concept writ large once again. Figure 2 below illustrates NAfME’s seven contexts in which such opportunities will inevitably arise:

Figure 2 NAfME’s suggested music learning contexts (Inspired by NAfME, 1991)

Practitioner profile

Whilst secure musical skills would undoubtedly enhance the ability of early years staff to deliver the kind of programmes advocated, so also would a facility in other arts disciplines, and much else besides. However, as discussed earlier, the central focus must always be children’s access to enhanced learning – and observation evidence clearly implies that, for instance, an inability to sketch like a professional artist rarely deters staff from encouraging young children to recognise, explore and reconstruct their visual world.

Whether a child’s innate communicative musicality is supported and enriched by a parent, childcare professional or even a childhood music education expert, NAfME suggest the essential qualities of the adults guiding each encounter remain the same, and must include a willingness to:

- love and respect young children,

- value music, and recognise that an early introduction to music is important in the lives of children,

- model an interest in and use of music in everyday life,

- show confidence in their own musicianship, however modest, realising that there are many effective ways to personally affect children’s development and musical growth,

- enrich and seek improvement of their own personal musical and communicative skills,

- interact with children and music in a playful manner,

- use developmentally appropriate materials and teaching approaches,

- find, create, and/or seek assistance in acquiring and using appropriate music resources,

- cause appropriate music learning environments to be created, and be sensitive and flexible when children’s interests are diverted from an original plan. (NAfME, 1991)

Whilst it is perhaps true that such an approach demands some focused effort from adults conditioned to a world in which our default mode is to be passive receivers of music, nevertheless we must surely take comfort from the fact that our children at least arrive in this world fully equipped to participate in, and gain from, a music-enhanced programme of holistic child development. Because, as Stein reminds us:

‘Children are born musicians, dancers, artists and storytellers … we just have to set the stage for creativity, learning and fun.’ (Stein, 2008)

… it’s just down to providers to do something about it!

John Cleary is a musician and former Head of Music who has also worked as a peripatetic instrumental teacher.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login