Child Development

Outdoor Landscapes: An Interactive Learning Environment

For early years children, the outdoor environment appears permanent yet flexible, reassuringly familiar yet brimming over with exciting new possibilities. In such a place the young child can enjoy living and playing wholly in the moment whilst building and reinforcing strong memories of events and experiences. As this personal data accumulates and starts to become broadly cyclical, so a gentle interactive learning journey begins to move the child towards a gradual understanding and appreciation of time and place, and so much more besides.

A diverse environment

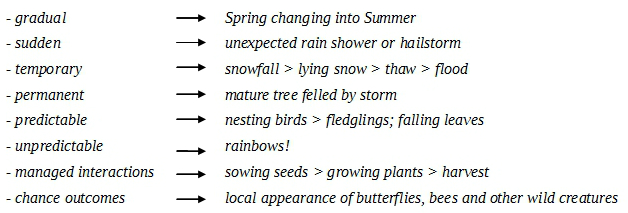

For childcare professionals, the outdoors represents the ultimate playing and learning resource offering an endlessly shifting kaleidoscope of engaging experiences which attract, fascinate and accommodate children at every phase of their development. Figure 7.1 explores just some of the freely accessible options a natural outdoor landscape area can provide:

Figure 7.1 The outdoor landscape: a diverse matrix of options and events

The natural world constantly evolves and each element interactively influences the rest: the seasons bring longer-term adjustments throughout the advancing year; weather patterns are reflected in the skies, whilst also touching the landscape and all its inhabitants; flora and fauna of all descriptions appear and disappear according to natural rhythms of their own.

One implication of this changing outdoor context is that conscious anticipation and planning for these naturally occurring events and phenomena is absolutely essential to ensure children gain the most from time spent playing and learning outside. Whilst that obviously includes suitable clothing and protection against the prevailing weather, other toys, tools and play-equipment must also be on hand and ready for action. To be truly effective, curriculum planning for the exterior classroom must be on par with the play and learning opportunities provided for any interior space.

Defining The Outdoor Classroom – Download Free eBook

Outdoors, children will naturally seek to interact with all that their play space has to offer. However, though that desire is constant, a moment’s thought will determine that the landscape itself is always in a state of transition, and a brief analysis of its shifting state underlines why it is such a richly diverse environment full of child-friendly rewards and challenges.

Outdoor changes can be:

Garrick (2011) describes these interactive options as examples of ‘children learning from first-hand experience in responsive environments’, and notes many others strongly supportive of this perspective: Montessori (1912) whose typical child was ‘a little explorer’; McMillan (1919) who encouraged children ‘to move, to run, to find things out’; and De Lissa (1939) who observed children’s delight in ‘experimental play’ with flexible resources.

Advocating early years outdoor provision in environments which are ‘dynamic, versatile and flexible’, Garrick cites three modern theory concepts – learning dispositions, a new sociology of childhood, and possibility thinking – which support this characterisation of an ideal outdoor learning space as an interactive, responsive environment.

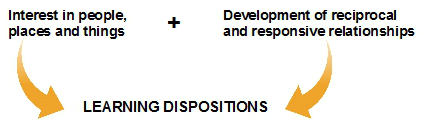

A theory of interactive learning dispositions

Developed by Margaret Carr (2001) for assessment purposes, the concept of ‘learning dispositions’ is summarised as patterns of behaviour, thinking, and interaction which help to ‘turn abilities into action’ and thus improve intelligent performance. Learning dispositions can be visualised as powerful learning tools which are optimised to support the holistic learning approaches of early years learners. As Figure 7.2 illustrates, a young child’s natural interest in ‘people, places and things’ and innate human inclination to develop ‘reciprocal and responsive relationships’ are tendencies which initially drive the development and refinement of learning dispositions.

Figure 7.2 Drivers which promote learning dispositions

For all learners, attitudes towards learning are closely associated with the acquisition of knowledge and skills. But for young learners in particular, this triad of features (attitudes, knowledge & skills) together form an initial, functional theory of learning which promotes five types of learning disposition. Shown in diagram form in Figure 7.3 – where they are listed as ‘taking an interest’, ‘being involved’, ‘persisting with difficulty or uncertainty’, ‘communicating with others’ and ‘taking responsibility’ – these traits are regarded as critical attributes which both encourage and influence the outcomes of early learning. Garrick identifies interactive playing and learning outdoors as a prime context for developing such learning dispositions.

Figure 7.3 Five learning dispositions (Inspired by Carr, 2001)

A new sociology of childhood

Most social theories consider young children to be ‘relatively passive’ absorbers and receivers of sociological influences. However, James and Prout (1997), and especially Corsaro (2011), have criticised this standpoint, not only on grounds of ‘generational inequality’, but because a significant body of research demonstrates that children are ‘social actors’ in their own right. Evidence for this view, Corsaro believes, shows that:

‘children are active, creative social agents who produce their own children’s cultures.’ (Corsaro, 2011)

Most childcare professionals will be aware of the tendency of groups of children playing together to develop their own elaborate rules, rituals, chants and conventions. Such peer cultures have been shown to be persistent features of children’s social behaviour with a very long history. Furthermore, Corsaro argues that ‘childhood’ must also be considered a permanent rather than temporary/transitional phase and thus a societal sub-group, which continues to exist even though its membership changes as individuals mature and move on.

Figure 7.4 Children playing together are creative, social agents (Inspired by Corsaro, 2011)

This new sociological perspective, illustrated in Figure 7.4, is a useful way to explore and value a key aspect of the world of young children, and a reminder that the outdoor playing and learning environment is a place where such creative interactivity can be regularly observed, and deserves to be fully supported.

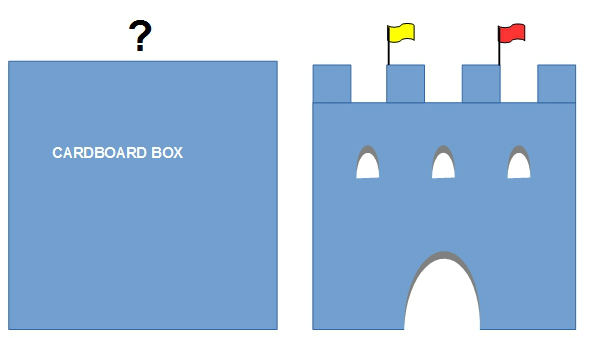

Creative possibility thinking

The third concept which is highly relevant to interactive engagement in outdoor contexts is Craft’s notion of ‘possibility thinking’. This is a supportive means of encouraging children’s creativity (see Figure 7.5) which the author explains thus:

‘Possibility thinking … essentially involves a transition in understanding; in other words, the shift from “What is this?” to exploration – i.e. “What can I/we do with this?”’ (Craft, 2002)

Anxious to clarify precisely where, and how, the core focus of this initiative must be directed, Craft goes on to comment:

‘It is important to distinguish between creative practice and practice which fosters creativity. In developing creative practice, we are nurturing imaginative approaches to how we work with children. In practice which fosters creativity, by contrast, our focus is mainly on ensuring that we encourage children’s ideas and possibilities, and that these are not suffocated.’

Figure 7.5 What does this do? (Inspired by Craft, 2002)

Professional childcare practice which truly fosters creativity is regarded as being inherently more valuable in that it is overtly ‘learner inclusive’. This feature is important because it clearly demonstrates that a child’s ideas are being taken seriously. As such, behaviour which involves ‘children and teachers co-participating in the learning context’ potentially has the highest motivational impact on child learners.

Possibility thinking in an outdoor setting can thrive in environments where flexible resources such as loose parts, PVC pipes, tyres, fabrics and similar are available to enhance the natural materials already on site. However, Craft believes that other features of the provision are considerably more important:

Posing questions – both those voiced by children, and implied by their behaviours, shows staff have ‘respect and interest’ and makes an essential contribution to imaginative outcomes.

Extended play – allows children time to become highly engaged in their play, sends a message about the real importance of their activities, and yields rich learning experiences for all.

Immersion– the extent to which children are supported to become deeply immersed in their play impacts upon the quality of experiential learning which occurs. Once again, staff attitudes are key to supporting and validating deep involvement.

Innovation – guiding children in their attempts to make playful connections, especially as regards the exploration and development of an initial stimulus, helps them towards a more fluent understanding of the process.

Being imaginative – when children are encouraged to be imaginative, they become more discerning about the quality of ideas, and also begin to influence the design of the task.

Self-determination and risk-taking – when children are encouraged to think independently, given plenty of time, encouraged to take risks in a secure setting and involved in decision making, the experience becomes ‘empowering and generative’.

Whilst no theories ever attempt to cover the totality of professional childcare settings, they do provide an authoritative means of evaluating some key aspects of early years provision. The three concepts of learning dispositions, a new sociology of childhood, and possibility thinking which Garrick has identified can contribute much to equipping children with tools for a lifetime of learning, giving children a sense they are valued stakeholders in society, and providing an experience with creative thinking at its core. It is hard to imagine a richer or more suitable context in which to deploy these interactive approaches to nurture 21st-century citizens than a diverse outdoor landscape where children can ‘choose, create, change and be in charge of their play environment’ (Garrick, 2011).

References

You must be logged in to post a comment Login