Child Development & Technology

The Impact of Technology on Social & Emotional Development

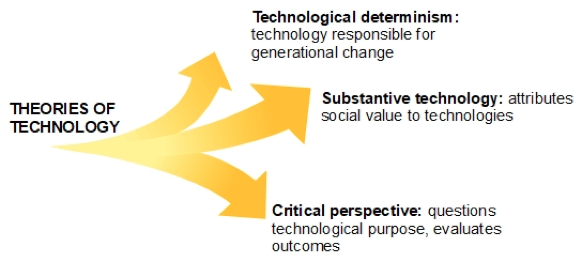

The use of technology is one of those areas of childcare and early years learning where conflicting opinions and ideologies seem to have become a permanent feature. And though some parents and childcare professionals may have given little thought to what actually drives their attitude towards how children interact with technology in the digital age, experts believe that most reactions to technological innovations can generally be assigned to one of three theories:

- technological determinism

- substantive technology

- a critical perspective

Technology in Early Years Education

As summarised in Figure 1, these accounts can reveal the underlying thinking which governs those opinions, and often prejudices, which many people hold dear. For instance, technological determinism can explain the reason for:

‘Assumed relationships between technologies and learning [which] tend to mirror technological determinist notions of cause and effect. Here, technologies themselves are often described … as having an almost inherent potential for informing young children’s learning.’ (Stephen & Edwards, 2018)

Elsewhere, those adopting a substantive approach will tend to accept that digital technologies are already embedded in our daily lives. For some that may be cause for celebration, while others may strongly disapprove and genuinely regret the abandonment of earlier modes of delivering early years education. As Scollan and Gallagher comment:

‘… access to technology for the under-fives has far outreached any research undertaken to fully comprehend long-term socio-emotional and cognitive effects, [thus] we find ourselves in a dilemma as to trust technology or fear it.’ (Scollan & Gallagher, 2017)

However, adopting a critical perspective towards any use of digital technology for young children demands an altogether more nuanced and evaluative approach:

‘… it is the degree of coherence between values and expectations and the purposes, behaviours and practices around technological innovation that influence the ways in which individuals and social groups react. When there is a mismatch between values and expectations and changing practices, accompanied by an assumption of technological determinism, then concerns … are more likely to be expressed.’ (Stephen & Edwards, 2018).

Broader Perspectives

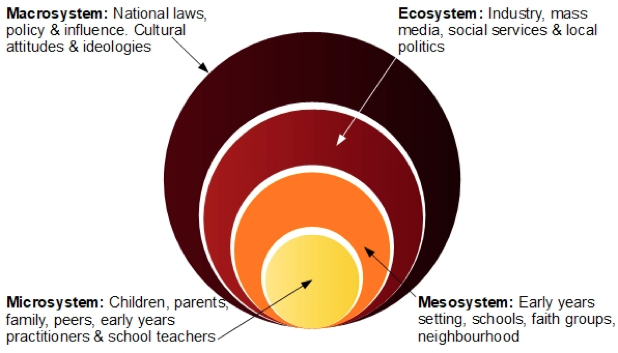

When considering the impact of technology on children’s personal and socio-emotional development, it is once again all too easy for adults to feel swamped by the pressure of diverse influences which play out in this context. So when looking to establish and manage child protection measures of any kind, the first stage is to find a way to conceptualise such influences. Scollan and Gallagher suggest employing an adaptation of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecology of Human Development (1979) as illustrated in Figure 2 below.

The essential message is to carefully consider the level(s) at which issues manifest themselves. So, with reference to the above model, an early years setting wishing to introduce technology might face a diverse range of barriers: there might be support from parents in the microsystem, yet resistance from the ecosystem at policy level (e.g. the local authority). Or equally, a local authority may be keen to introduce technology in a setting, but microsystem practitioners may resist its introduction – perhaps because of a lack of training opportunities.

Local Digital Culture

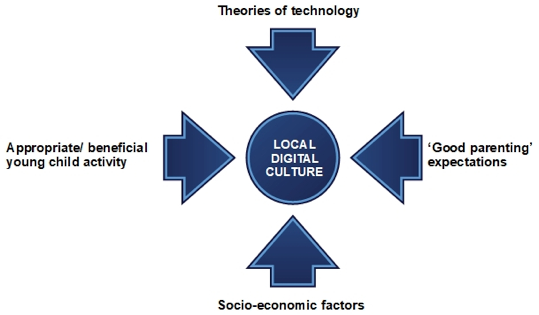

At family level, where so much of the supportive early motivation and opportunity for young children to embark upon a digital lifestyle occurs, the factors described above act together to create a localised digital culture. So theories of technology will influence whether a particular set of parents support (or resist) technology because it drives change, substantively accept technology just because it is perceived to achieve some goal, or critically evaluate the options available.

Beyond this, there will be community derived ideas about what ‘good parents’ are expected to provide for their younger children, as well as socio-economic factors which will impact upon every family. On top of all this, any family will have their views about what is a suitable device and material to be accessed by pre-school children.

As Figure 3 illustrates, the result of this blend will interact accordingly to produce a locally defined culture which will guide each family’s decisions about the extent to which their youngest children are given encouragement to access technology within the home.

Bright Lights and Bells

As far back as 2001, Levin and Rosenquest were highlighting the possible negative impacts of a proliferation of electronic toys for the very young. According to this (determinist) view, the quality interactions afforded by traditional toys were being increasingly displaced by ‘bright lights and bells’. This somewhat throwaway phrase nevertheless can be seen as representing a persistent thread in much of the research into the use of technology by pre-school children.

Regardless of whether the study outcomes support or undermine the effects of digital devices, there has often been an unhelpful tendency to put forward overly simplistic claims. Stephen and Edwards, for instance, comment that:

‘… gender, personality factors and the priming effect of the behaviour of others are all suggested by these historical studies alone as factors which intervene to make a difference to outcomes in a way that is not yet evidenced in all contemporary discussions about young children’s engagement with digital technologies.’ (Stephen & Edwards, 2018)

Even today, many associated with the childcare sector appear surprised that young pre-school children should want to access technology devices. This might seem to imply that such technology should really be reserved for adults and teenagers. However, advances like touchscreens, graphic interfaces and the Internet of Things, plus the absolute certainty that a fluent understanding of digital technology is an absolute essential for 21st-century children, make such a negative stance entirely redundant. For most people of any age, technology is at our fingertips, or at least within easy reach.

Evidence supporting a ‘balanced’ approach?

Many doubtless well-intentioned studies of young children and their access to technology have been accused of bias. Sometimes it is apparent in reports such as Chaudron (2015) which comments on ‘little use of digital technology … to support explicit learning or education.’ Such remarks seem to imply that young children’s access to technology is only worthwhile if there is some inherent educational goal attached to the package or device. While this determinist approach has already been critiqued, a more important point is that the expectation for a desirable outcome so often seems to rest with the technology itself, rather than with the results of the human interactions occurring in the planned learned context in which that technology was chosen as a tool to enrich those human interactions.

Other studies which have looked more comprehensively at how access to digital technology has impacted upon the behaviour of young children seem to present more measured outcomes. For instance, when Vanderwater et al (2007) investigated the time children who engaged with digital technology spent being read to or participating in outdoor play, it was found that whether or not the child obeyed or exceeded the US Academy of Pediatrics screen time guidelines made no difference to the time devoted to reading or playing.

Another study (Moore, 2015) focused on the imaginative play practices of children spanning three generations. The outcomes demonstrated that seven play practices – such as the use of bedrooms and trees for imaginative play; making use of found objects; the need to find a quiet, private place; and the pervasive influence of popular culture, etc. – had remained stable over four decades. In addition, three changes to imaginative play practices were noted in the most recent decade: the use of toys in the performance of imaginative play, the degree of privacy sought, and the availability of play locations.

Safeguarding Children

One area where there is sure to be agreement among stakeholders in the childcare sector is the need to avoid children being exposed to ineffective elements which may prove to have a negative, undesirable, or even malign influence. Yet adults charged with the task of reviewing devices, software etc. to be used by young children at home or in an early years setting are often at a disadvantage because the technology element to be reviewed must be carefully assessed from multiple perspectives. Among other considerations, the primary requirements will be to understand where, what and how the children will be learning during their planned digital exploration.

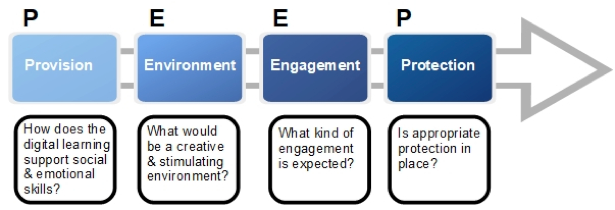

To meet this important need, Scollan and Gallagher recommend using the PEEP assessment model (see Figure 4 below) to gauge how any particular provision could be used to develop digital skills which will positively impact upon children’s personal, social and emotional development.

A PEEP assessment is a comprehensive series of questions which looks at four areas:

- Provision

- Environment

- Engagement

- Protection

The authors believe this will create a ‘pedagogical lens’ to identify any challenges which may later arise during the proposed digital interactions:

‘The PEEP model aims to provoke reflection regarding communication, actions and reactions, emotional literacy and physical movement experienced by children during micro transitions and digital use. Reflections on practice, digital expectations and values are presented in the model …’ (Scollan & Gallagher, 2017)

Digital immigrants and digital natives

Though some observers argue the concept is finally approaching its sell-by date, Prensky (2001) coined the terms ‘digital immigrants’ and ‘digital natives’ to distinguish respectively between adults who have adopted digital technologies, and young children born into today’s digital world. In the context of using tools such as the PEEP model, these descriptions can sometimes help to understand the emergence of generational conflicts and other problems and misunderstandings which can otherwise easily occur.

For instance, Rubin has highlighted the recent emergence of a ‘digital realm … so immersive that it is neurologically indistinguishable from the outside world.’ (Rubin, 2014b) This feature, and other new-wave technologies, can eventually leave most adults feeling exhausted and perplexed. Yet pre-school children, recently arrived in a modern, media-rich environment, seem to interact with such features, and transition between real and virtual worlds, much more comfortably. Nevertheless, children are children, and they will occasionally get such transitions wrong – think of coming straight from a birthday party to a church service! That’s where a PEEP assessment can often flag up contexts in which such issues may arise.

In conclusion, and revisiting the point that pre-school children are born digital natives, Scollan and Gallagher comment that ‘new and evolving technologies are important to the personal, social and emotional development of children.’ Thus, the authors firmly believe, ‘we will need to accept that they are here to stay.’ (Scollan & Gallagher, 2017)

You must be logged in to post a comment Login